Brands

Liquid Death’s founder explains his hardcore canned water startup

“We’re weird, and it’s a weird brand.”

People freaked out a bit last week when Liquid Death, a comically over-the-top-branded canned water startup (slogan: “Murder your thirst”) announced that it had raised $1.6 million in seed financing, led by Science, the incubator behind Dollar Shave Club.

It was kind of the perfect storm for the internet outrage set: A scruffy-looking white guy (founder and CEO Mike Cessario, a Los Angeles-area creative director) had been handed a lot of money (Liquid Death has now raised $2.25 million) from Silicon Valley-types to sell the ultimate free, natural resource (spring water) in a tall-boy can ($22 for a case) with a dripping, human skull illustration on it.

Also, it’s called Liquid Death.

So it wasn’t exactly surprising when a lot of the criticism seemed more accusatory and hostile than the typical startup-funding eye rolling: Why do VCs insist on backing this kind of bro shit?

Is it sustenance? Art? A get-rich-quick scheme? In bad taste for the school-shooting, internet-bullying, scary-president era? Or just what America’s youth needs to stay hydrated and stop drinking sugary crap? Also, why should Coke and Pepsi be the only ones making money off $2 waters?

The initial Business Insider post — “A former Netflix creative director just got $1.6 million from big names in tech for Liquid Death, which is water in a tallboy can” — is now approaching 80,000 views, which, I assure you, is way more than the typical startup-funding post.

Helen Rosner, the reliably-assertive-but-generally-in-touch-with-the-zeitgeist New Yorker food writer, tweeted a few dirty jokes, and then, “I’m sorry, this product is honestly so stupid and so insulting and so painfully shameful for all involved that I really cannot go on.”

Eater even made fan fiction.

It had been a while since I’d seen such a strong reaction. So I got Cessario on the phone to talk about the backlash, how he got started with the brand, why he’s going into the water business, and what he wants from all of this. I wanted to let him go long, so that’s below.

My take?

It is weird, indeed, that a substance you need to consume to survive is called Liquid Death. I realize that’s part of the point. And it’s obviously going for a different sense of humor than the one I’ve settled into in my mid-to-late 30s. Would I drink it if I needed to? Sure. (It apparently tastes like water, which is a good sign.) But I’m not running out to join the street team.

Also, this is a totally different business play than Dollar Shave Club, which disrupted a high-margin industry with a low price and vastly improved customer experience. This is plain water in a different container, for the same price, with a skull on the can.

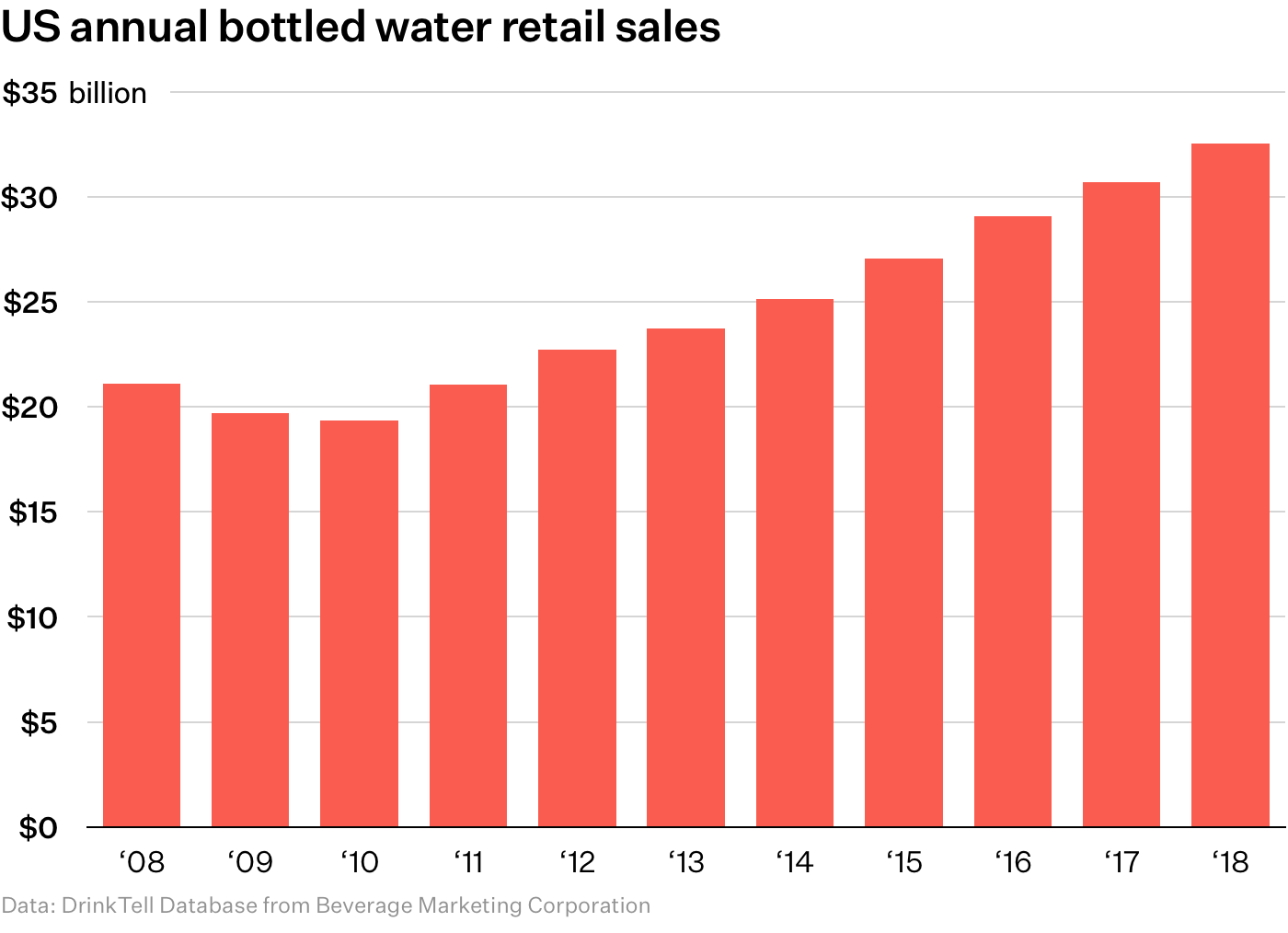

But: People buy a lot of bottled water, energy drinks, body spray, and cheap beer. Bottled water retail sales in the US passed $32 billion last year, according to Beverage Marketing Corporation. There is money to be made here, and perhaps opportunity for an edgy brand to claim some of the market. And the recycling-friendly aluminum can is not a single-use plastic bottle, which is timely.

Chart of the Day

So this will be an interesting execution and marketing study. In this era of niche consumer brands, do enough people want to murder their thirst? Is this a lifestyle brand that people will rally around?

Liquid Death, for what it’s worth, is currently the no. 10 best-selling water on Amazon, behind some cheap Nestle stuff and fancier brands like Essentia, Evian, Perrier, and Fiji. The company sold out of its first production run of 150,000 cans in less than 8 weeks, Cessario says.

In addition to the web, Liquid Death is now available in about 60 bars, venues, tattoo parlors, barbershops, and coffee shops. It’s testing well in four 7-Eleven stores, Cessario says. And he’s also looking into other healthy beverages, potentially including functional ingredients.

Here are the highlights of our conversation, lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

On last week’s attention:

“I think it’s pretty clear that Liquid Death is not a normal brand and we’re not really normal people. We’re weird, and it’s a weird brand. If you search the hashtag #liquiddeath on Instagram, you see all different kinds of people posting. People would say, ‘Oh, well something like Liquid Death, that’s only going to appeal to metal-heads and punk rockers’. It does appeal to them, but we were surprised to see a massive audience of people. We have old ladies coming up to us saying, ‘This is just the coolest thing, this is so fun’.”

On the inspiration behind Liquid Death:

“Growing up, I played in punk rock and metal bands, and in a brief part of my career, I worked in the action sports industry. And I always noticed that energy drinks and unhealthy things basically own that space. And they’re the only beverage or food companies that are investing in that culture. Meanwhile, me and a lot of my friends, we’ve never really drank energy drinks. We were vegetarians. We were about health.”

“I always had this idea: What would happen if you had a really healthy product that was marketed just as over the top as some of these other brands? The thing that people don’t drink enough of — especially younger people — is water. And if you look at the bottled water cooler in a convenience store and what that looks like — and then you go look at the beer cooler or the energy drink cooler — it’s not rocket science to realize why way more young people are drinking these other things and not water. And as much as marketing is marketing, and it shouldn’t matter, the reality is, it does matter.”

“The people who really get Liquid Death and love it, they get the sarcasm. They get that we’re not actually being serious. We don’t actually think water is tough. We’re kind of making fun of extreme marketing in some of the unhealthy spaces. An energy drink is mostly water and then a little bit of sugar and a little bit of caffeine. Somehow that makes it okay to market it over the top. But if you take out that spoonful of white power, now it’s so crazy to give something extreme branding.”

On how Liquid Death tested the waters:

“We launched it on social media first before we had actual product just to see what the reaction was. We shot a video for $1,500. We put about $600 of paid media behind it. We ended up getting almost 3 million views after a couple of months. We were getting all these direct messages on Facebook from distributors and 7-Eleven owners saying, ‘How do I get this? This is awesome, how do we carry it?’ So then we realized, okay, this is probably going to work.”

“I like to compare it to the way the entertainment industry works where every TV show, pretty much, you make a pilot first. You find some low-cost way to see if something is going to be good, and worth investing a lot more into, before you go all-in on it.”

On getting started:

“Beverage is an insanely capital-intensive space. Especially if you’re putting stuff in cans. The minimums are really, really high. If you want to print an aluminum can, the minimum quantity you can order is 250,000. So it takes a significant investment just to do anything.”

“The other thing that we didn’t realize is that putting non-carbonated water in aluminum cans without preservatives is a really difficult thing to do, that doesn’t really exist in North America. There’s not a bottler or canner that can really do it. We ended up going with one we found in Austria. When we visited them, their facility was absolutely immaculate. The water was actually really, really good.”

On the beverage industry:

“There’s a lot of moving parts and complexities, especially when you start getting into the more traditional channels. Right now we’ve only been online. We’re just starting to dip our toes into the more brick-and-mortar outlets, talking to convenience stores, retailers, and things like that. And everything that goes into beverage distribution — different rebates and things that they want, and slotting fees where you have to actually pay to be on the shelf in a store.”

“We have some good advisors and investors who come from the [consumer packaged goods] space. The co-founder of Perky Jerky, the jerky brand, has been super helpful. And we work with a sales team now called Cascadia, run by Bill Sipper, who’s a pretty well-known beverage guy. They know all the ins and outs of this stuff and they’re helping us with the brick-and-mortar stuff right now.”

On whether he’d rather just sell direct to consumer:

“We would love to sell direct only, because it’s letting the market decide if they want this. I think the drawback is, as most beverage companies are finding, the cost of shipping a heavy case of water is really high. The only way that it could be sustainable for us is to sell a case for $21.99, which includes delivery. Most people don’t realize that everything on the internet that says ‘free shipping’ is not really free shipping.”

“Water is one of those things, too, ultimately, we think we’re going to have to be in traditional channels. Half the reason bottled water exists is for the convenience factor, obviously. It’s not like something that you want to have to order on the internet every time you want it.”

On the Liquid Death brand message:

“What we’re trying to do is not very different than what, like, a punk brand would do, or a hip hop group would do. When Eminem first came out and dropped his first album, it made waves — there was never anything this vulgar or about this subject matter in this space. For me, none of that sort-of subversive thinking has ever been able to make its way into the packaged goods product space. Because the gauntlet that you have to go through to even get a product to market is so much harder than music. And there’s not a lot of people that come from the world of metal or punk who have been able to navigate that.”

“We want it to be funny. At the end of the day, water really is water. There’s people who are against bottled water, who never want to buy it — that’s fine. There’s a lot of people who do buy bottled water. Would you rather give your $2 to this big, cold, faceless company? Or to this more art-, humor-driven company?”

“What I’m most excited about is: If we can grow this brand and make it big, then we can elevate all kinds of other weird artists, musicians, entertainment — the kinds of things that people are really interested in and think are funny, but would probably never be supported by a big brand, because they’d be too nervous to support it or champion it. We’re excited to be the ones to champion that sort of stuff.”

On the funding backlash and sexist messaging:

“I understand it. There’s a huge problem with the Silicon Valley everything. The fact that female founders are not getting the kind of investment that male founders are. We totally recognize that.”

“We’ve been very cognizant with our brand to try to not be sexist. A lot of energy drink companies, they’ve got bikini clad girls that go around giving out cans. We never want to do anything like that.”

“I think women are actually our fastest growing segment. I think there’s a lot of women out there who are stoked on the fact that there’s a brand that is a product that they like to drink and consume but has a totally different vibe to it that they identify with, that they think is funny, they think is cool.”

On the long game:

“We want to grow this brand and kind of become like the Red Bull of water, in a sense. What I really respect about Red Bull is they blur the lines between an entertainment company and a [consumer packaged goods] company. Before Red Bull came out, nobody was giving money to skateboarders and BMXers and motocross guys. They saw something and were able to support and elevate that industry to what it is now.”

“I think we’re a little bit more on the art and music side of things. But in terms of internet culture, like YouTube creators, people who are putting out their own crazy cartoons or content. Or the fact that someone can make a podcast that’s vulgar, and you can actually get tons of followers — you’re not censored anymore. This whole world of the democratization of content is really exciting to us. And if we can be a brand that grows and champions that, we can kind of blur the lines ourselves between being a water company and being an entertainment company.”

Hi, I’m Dan Frommer and this is The New Consumer, a publication about how and why people spend their time and money.

I’m a longtime tech and business journalist, and I’m excited to focus my attention on how technology continues to profoundly change how things are created, experienced, bought, and sold. The New Consumer is supported entirely by your membership — join now to receive my reporting, analysis, and commentary directly in your inbox, via my twice-weekly, member-exclusive Executive Briefing. Thanks in advance.