Brands

Foxtrot is the store that every neighborhood deserves

Can Chicago’s upmarket convenience chain scale across the country?

It’s late on a Tuesday morning in downtown Chicago and the space where I’m hanging out feels alive. People are reading, drinking coffee, chatting, taking calls, getting in an early lunch at the laptop. There’s free wifi, lots of light, and a big leather couch if that’s your thing — there will be wine later.

But this is not a hotel lobby, coworking space, or café: It’s a Foxtrot, one of the most interesting and best executed retail concepts I’ve seen in a long time — now in the early stages of what could become a national expansion.

I’d been hearing more about the company over the past few years, as Foxtrot — usually described as a modern convenience store — started to expand into new cities and invest in things like private-label products and nationwide gift-box e-commerce.

But Foxtrot, which launched its first retail location in 2015 and recently opened its 21st, is more than just another corner store or delivery app.

And after recently returning to Chicago — its hometown and mine — to spend some time in its newest and most ambitious stores, Foxtrot’s potential clicked for me.

Here’s some of what I learned.

1. Foxtrot is a place, and a feeling

Foxtrot is a few things: Upscale convenience store, third-wave coffee shop, and wine boutique, digitally equipped for pickup and delivery. Each of these pieces is important, and I’ll get into the details.

What’s unique is how Foxtrot has integrated all of these into a neighborhood retail space that’s welcoming and fun — a “third place” where you might actually want to spend time; where there’s been consideration and creativity applied to the user experience.

“The whole vibe of the stores is that it’s this warm, neighborhood spot where — yes — you can pop in and grab something quickly if you need to,” Foxtrot co-founder and CEO Mike LaVitola explains.

“But it’s a place that you’re excited to go to,” he says, “because you’re going to find something cool, there’s going to be some interesting music on, the folks behind the counter are going to be able to turn you on to something new.”

“Sort of the opposite of what you would get at a traditional corner store, where it’s cold, fluorescently lit, and it’s ‘get in and get out’ as quickly as you can.”

Foxtrot stores are high-end without feeling pretentious, in locations that seem intentional. There’s a spirit of hospitality that feels more like a restaurant than a grab-and-go market. For example, there is more seating than you’d expect — often between 30 and 40 seats — including outdoor patios. There are fun touches at some locations, like a walk-up “wine window.” Bathrooms exist and were clean during my visits. Wifi is free and noted on the menu board.

This sort of stuff — thinking about what people actually want and how every aspect of the retail experience should be designed — sounds obvious. But it’s rarely done well, particularly among chains, where there’s little to no taste, excitement, or ongoing innovation.

And especially as quick-service commerce investments these days tend to gravitate toward faceless, soulless, land-grabbing delivery services.

At Foxtrot, it feels like the people in charge actually care about the big picture and the details. And that’s why anything else here is worth paying attention to.

2. Foxtrot is a great store

Crucially, Foxtrot gets the main thing right: It’s building a convenience store for the modern consumer. For The New Consumer.

This means: A curated assortment of more than a thousand groceries, beverages, household items, and prepared foods, from the cutting-edge and adventurous to the hit staples. The chance to discover new brands and products and also to stick with comforting favorites. A current approach to what’s good to eat and drink, with the opportunity (but not obligation) to eat healthy. And a mix of brands, from tiny local startups to global household names.

At Foxtrot, for instance, you can buy new products from cool brands, like Momofuku instant noodles and tins of Fishwife smoked trout, but you can also buy a can of Campbell’s chicken noodle soup. You can buy exclusive Snickerdoodle Funfetti cookie kits made by local Chicago pastry legend Mindy Segal, or you can buy a box of strawberry Pop-Tarts. You can find a $39 bottle of Rosie Assoulin’s lively natural Vivanterre orange wine, or you can buy an $11 case of Bud Light.

I find some of the high-low juxtaposition amusing, but it’s really about providing choices to a broad group of consumers in a variety of situations.

Some days you might have the time and resources to cook dinner from scratch, and Foxtrot offers things like boneless chicken thighs, pre-sliced veggies, Rancho Gordo beans, local tortillas, spices, and sauces. Other days, you might just want to heat up some mac and cheese — and you can take your pick from at least a half-dozen packaged, frozen, and heat-and-eat options.

“It’s important to not push customers to one way or the other,” Mitch Madoff, Foxtrot’s SVP of private label and supply chain, explains, “but to meet them along their journey.”

3. Foxtrot is a legit café

This was a surprise. When’s the last time you had a great cup of coffee from a convenience-store chain? But Foxtrot is actually a real third-wave coffee shop, partnering with local roasters, like Metric in Chicago and Vigilante in DC, and, in my limited experience, serving dialed-in drinks.

In the morning, it offers breakfast tacos (a bit of Austin influence, where LaVitola and co-founder Taylor Bloom used to live), sandwiches, and toasts, including a classic avocado toast on local sourdough and a smoked salmon version with “Everything” seasoning.

Foxtrot’s approach to sweets is generally “yes,” and that’s on display in the pastry case, where you’ll find locally made bagels and croissants, but also “fruit loop” cookies and brightly colored Hardbitten pop tarts in flavors like Nutella Raspberry, topped with sprinkles (calorie count not listed).

For lunch, there are both grab-and-go and made-to-order salads and bowls, including a spicy mushroom miso bowl and an Elote Caesar Salad with roasted corn and masa croutons.

And in the evening, there’s wine — by the glass or bottle, no upcharges — with snacks from the prepared-foods fridge, including marinated olives and charcuterie trays. (A new afternoon café program and pizza are in the works.)

“The stores at night are, like, first-date incubators, which is really funny,” LaVitola says. “The music’s good and it’s way cheaper than going to a real place. If it’s going well, you can go to a nice restaurant. If it’s not, you can bail and not have spent that much.”

Coffee — and, more broadly, the café — is a more important part of Foxtrot’s strategy than I had gathered from a distance.

And it makes sense: As a habit-forming ritual, coffee can get customers into the store on a regular basis, both for a caffeine boost and to potentially purchase food or other items. The company has already sold almost a million cups so far this year, and the café — including prepared foods — represents roughly 30% of its business.

It’s also a huge operational challenge — employing cooks and training baristas — and it doesn’t always hit. I was excited about my burrata chopped salad, but the garlic vinaigrette overpowered everything and followed me around for the rest of the day.

It’s hard to run a small restaurant, let alone dozens, especially as just one portion of an overall concept. But compared to the typical American convenience store’s hot dog rollers, cold-cut sandwiches, and fried stuff, there’s ambition here.

4. Foxtrot is developing interesting in-house products and brands

Like most retailers, Foxtrot is increasingly investing in private label products and in-house brands.

Unlike other retailers, Foxtrot has hired Madoff — who previously ran Whole Foods’ 365 brand — to do something more sophisticated.

It shows. Foxtrot isn’t only making cheaper, higher-margin versions of commodity products, but is also using its point of view — and what it knows about its customers — to make new things you can’t easily get elsewhere.

These include Foxtrot-branded roasted banana and caramel ice cream — full-fat, full-sugar, and addictive; incredible spicy pickle potato chips; and a comically unhealthy, top-selling line of bagged sweet snack mixes, from Peach Emoji gummy mix to Cookie Monster chocolate mix.

This is useful for unit economics — private label now represents about 40% of Foxtrot’s revenue — but also to stand out in a world where most food retailers carry most of the same stuff.

“It’s really the only differentiator left,” Madoff says.

The company is about to launch its first line of private-label candles, branded Little Thrills, and has made bath bombs under the name Best Bubs.

But its moves into private-label alcohol, led by Dylan Melvin, perhaps serve as some of the best examples of the Foxtrot POV:

- Sun Lips Rosé, a $22 easy-drinking bottle with a cute label and twist-off cap, that would be welcomed at any Chicago yuppie backyard bbq, but isn’t garish or tacky. (“This is our number-one selling rosé, by about 100%” over the next-best, Madoff told me in May.)

- Play Nice Espresso Martini, a $33, fun-looking, gift-worthy bottle of ready-to-drink espresso martini — local vodka and Metric cold brew coffee — that shows it can quickly follow trends with a playful yet potent exclusive rendition. (“Our number-two selling spirit in the entire category,” Madoff notes.)

- Mouthy “Head to Toe” Cinsault, a $27 bottle of chillable California red, approachable but with some complexity, produced by winemaker Samantha Sheehan, that you can bring to a dinner party and doubles as an aspirational conversation starter: Just what is whole-cluster wine, anyway?

These exclusive products help solve consumer needs, for things like high-pleasure ice cream or mid-tier French rosé, driven by customer preferences and data.

(As an example, here’s how Sun Lips Rosé came to be: “We sell a ton of rosé in the summer,” LaVitola says. “We had a bunch of bottles, $15 and under, that were really productive. We had one bottle at $25 that was really productive. But we couldn’t find anything in that middle tier that’d work for us. And we knew from our data: Customers in this price point want something super super dry, pretty pale, and they prefer something from France.” Foxtrot tested options, sourced the wine, designed the brand and label, and voilà.)

But, crucially, these products also shape and build out the Foxtrot world: They show customers what they’d make them if they could make them anything — from the concept and the ingredients to the aesthetic and price — and what sort of ride they’re in for if they become Foxtrot loyalists.

And they give the company things to talk about that other stores simply don’t have — another important factor in today’s digital marketing era, where storytelling and media frequently drive discovery and consumption.

Almost every grocer has some sort of private label program, but the ones that do it best — Trader Joe’s, Costco, Whole Foods, Target — know that they’re building the brand with each new product, not just filling shelves or squeezing margins.

Foxtrot, so far, really seems to get that.

5. Foxtrot is half digital, with a clever loyalty program

Before Foxtrot opened its first store in late 2015, it was initially founded two years earlier as an online-only convenience delivery service.

E-commerce remains a huge part of its business and strategy: Digital, including pickup and delivery, represents about half of its revenue. Foxtrot wants customers to think of it first, whether they’re walking around the neighborhood or ordering on their iPhone.

Today, Foxtrot retail locations also operate as fulfillment centers. This allows the stores to generate more revenue than if they were only supporting in-store sales (and therefore to pay back their investment costs more quickly).

It means the stores can also serve as marketing vehicles for digital, with signage and other in-store features — pay with QR code to earn rewards, order-ahead for faster coffee — driving adoption of its mobile app. And it allows Foxtrot to experiment with things like digital-only promotions and pricing.

What’s unique here is that Foxtrot’s digital experiences — its app and website, developed mostly internally under its co-founder and CTO Taylor Bloom — are actually good.

In my experience, they’re as considered and well-designed as its retail stores, from the product selection to the merchandising. Sometimes, the company cuts a corner — not displaying nutritional info or a menu item’s full list of ingredients — but in other cases, goes above and beyond with the sort of storytelling that many peers simply wouldn’t do.

One nice detail is that parts of Foxtrot’s app, like elements of its stores, are programmed to the time of day. In the morning, as you open the app, it features its breakfast menu, reducing the number of taps required to order a breakfast taco. Around noon, it’s lunch items. In the afternoon, snacks and wine. And heading into evening, it switched to “quick & easy” dinner meals.

This is a little thing that seems obvious, but it reduces friction, increases contextual relevance, and just feels thoughtful — mutually beneficial to user and merchant. Other apps don’t make this feel as natural.

Most legacy retailers, meanwhile, have lousy, boring digital services, heavily relying on white-label software or outsourcing to marketplace providers like Instacart and DoorDash, which then own the customer experience and relationship. Trader Joe’s, notably, still doesn’t offer e-commerce.

For Foxtrot, this competence is expensive, but, done well, is a long-term competitive advantage. Consumers want fast, frictionless shopping services that are easy to use and reliable. I believe they also want services that represent a brand’s worldview, from the features to the design to the voice.

If used correctly, this should allow Foxtrot to do things better and with more control, from knowing inventory levels to merchandising and recommending products. That should create a superior customer experience, drive loyalty, allow for more differentiation, increase sales and margins, and generate useful, proprietary customer data.

One big piece of Foxtrot’s digital strategy is its Perks loyalty program, which bridges its physical and digital.

In its current iteration, if you spend $100 at Foxtrot over the course of a month, you unlock a handful of benefits, including a free in-store coffee every day, free delivery on all digital orders, discounts on drinks, and “all-day happy hour” pricing in select stores.

You can imagine how this might encourage someone — particularly someone who enjoys free coffee — to favor purchasing from Foxtrot across both physical and digital channels.

It’s also an example of how the company is able to get more leverage out of its café program: In this case, giving away a free cup of specific, low-cost coffee drinks — and subsidizing the rest of its high-margin drinks menu — to encourage daily store visits. This then drives even more spending and habit-building.

Perks customers spent $155 on average in May, split roughly evenly between digital — where they place larger orders than non-Perks customers, enough to justify the cost of free delivery — and smaller but more frequent in-store purchases.

This fall, the company plans to launch a new version of Perks, “a greatly expanded program that speaks to a lot more consumers,” LaVitola says.

6. Foxtrot and the future of convenience

If Foxtrot sits on one end of the future-of-convenience spectrum — designing beautiful stores with copious seating — at the other end is GoPuff, the app-based convenience delivery service that launched in 2013 and spent the past couple of years in hyper-growth mode. GoPuff says it now delivers to more than 1,000 cities, and — after moving too fast — just laid off 10% of its workforce.

A quick spin through GoPuff’s app reveals a service that has some overlap with Foxtrot’s selection, but is much more mass-brand and mainstream: Where Foxtrot is promoting $10 pints of Jeni’s ice cream, GoPuff has a $1-off sale on Blue Bunny cones and bars. Foxtrot does private-label for “whole-cluster” chillable red wine and fancy candles; GoPuff’s in-house brand, Basically, does cheap water bottles, toilet paper, and snacks.

The future is obviously some of both of these.

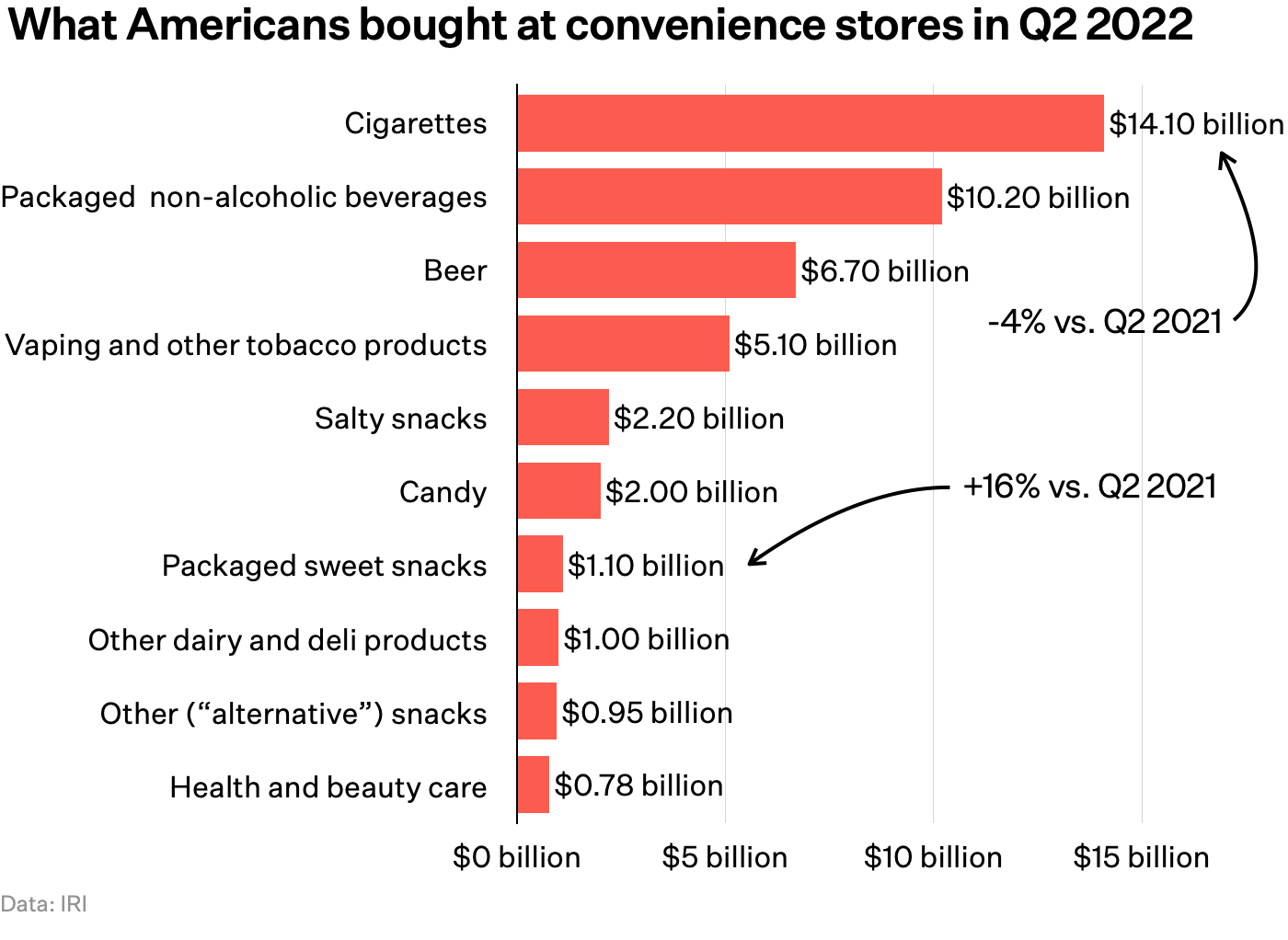

The convenience market is huge — around $170 billion annually in the US, growing slowly, and ready for reinvention. A big piece of the market is attached to gas stations — which will almost certainly go into long-term decline as more people switch to electric cars — and tobacco and beer represent more than half of US convenience channel sales, according to IRI.

Chart of the Day

While some incumbents are beloved — hello, Wawa nation — many others feel outdated and replaceable.

(I could, and should someday, write an entire separate article about the future of the gas station. Instead of refueling for a few minutes at a pump, more people will need to top-up for an hour during a meal, meeting, or shopping trip. Sounds like an opportunity for a Foxtrot with a parking lot — and many other concepts.)

The bigger picture is that the growing prevalence of e-commerce in grocery and convenience — accelerated during the pandemic — will continue to change the way people shop for food and beverages, via a huge, ongoing share shift between channels and merchants.

Most grocery shopping still happens at grocery stores — in the store — but it will increasingly move elsewhere, to aggregators like Instacart and DoorDash; to online grocery specialists like Thrive Market; directly to brands; and to innovators like GoPuff and Foxtrot. In the digital realm, “convenience” is a feature and a service, not necessarily a brand or class of merchant.

Over time, this will further shake up the broader $1+ trillion US grocery market, with opportunity for both digital-only and retail-hybrid entrants.

What excites me the most is when a brand does both physical and digital well.

I want a great store with a modern, opinionated assortment of food and drinks, household items, wine, coffee, etc., that’s a place I actually look forward to visiting; where I want to spend time. There aren’t enough of these, and as I do more of my “stock-up” shopping online, a welcoming physical space is still the best for discovery, community, and entertainment.

I also want a great digital experience, where I can get the same things brought to me, quickly and consistently — and, ideally, relatively economically — when I don’t have time to visit the store.

Foxtrot, of course, isn’t alone in trying to create this. Multiple readers pointed me toward Depanneur, what’s apparently an excellent convenience store (and bagel bakery!) in Copenhagen. In New York, Starbucks is testing locations with tiny built-in Amazon Go convenience stores. (Nice seating, weird assortment, and… still Starbucks coffee.) And there will always be great local grocers that choose not to expand for one reason or another: I can never get enough Bi-Rite when I’m in San Francisco, and I frequently miss my old Foragers in Brooklyn.

I think Foxtrot, though, could work in most cities, and I’d be excited to have one in my neighborhood.

Now for the hard part: Figuring out how to eventually scale into a national brand — and build a large, profitable business — without losing what makes it special.

7. How big can Foxtrot get?

“The closest comp — without sounding crazy — to us, is Starbucks,” LaVitola says. “We don’t have nearly that many locations. But that kind of ubiquity.”

That’s an aspirational target — there are more than 17,000 Starbucks locations in North America alone — but the reality is that Foxtrot isn’t yet in high-growth mode.

“For us, we’ll probably open up one — two at most — major new markets a year,” LaVitola says.

Today it has 15 stores in Chicago, two in Dallas, and three in the DC area. The plan is to more than triple in size over the next two years, opening 50 new stores during that time.

Rather than prioritizing expansion into New York and LA, Foxtrot is looking at cities like Miami, Nashville, and Houston. It’s also building both smaller- and larger-format stores, which can serve different types of buildings and neighborhoods and complement each other in covering a city.

Austin is its next market, planned for this fall, including a store that LaVitola is very excited about: An old market in a “super f***ed up building from 1920,” surrounded by live oak trees, “in the middle of this neighborhood I used to live in — it’s just, like, exactly what the brand is.”

That idea of ubiquity — driven by density — is more important to the company than putting flags across the country. “We would always prefer to open a store in a market we’re in than to go to a new city,” he says.

One problem is that the types of locations it wants are rare. “It’s not like there’s ten amazing corners in Chicago just sitting there vacant,” LaVitola says. “In a city, there might be two to five a year that fit all of our criteria. So to grow at the pace we want to, that necessitates opening up a market or two every year.”

Another challenge is that the sort of feeling that Foxtrot is going for — that it really belongs in a city and neighborhood, and isn’t just a carbon-copy global clone — takes time to get right.

“It takes us 18 months or so to really get the lay of the land, get the market strategy right, meet the local makers.”

I won’t dwell on the tension between a well-funded national chain entering a market or neighborhood with popular local corner stores — that’s capitalism. But for Foxtrot to provide an outsized feeling of authenticity, that process is necessary — and also limits its pace of growth.

As I’ve catalogued, Foxtrot is trying to do a lot. That’s what makes it interesting, but scaling each of these elements — while improving quality over time, and further building the brand — is going to be tricky.

My sense is that the café is going to be a particular challenge. Staffing and training is hard enough for fast-casual chains that only do foodservice, let alone when it’s just one piece of many, with both commissaries and in-store kitchens.

When Foxtrot gets bad reviews, it’s mostly for ops stuff: Messed up orders, issues with staff, late deliveries, poorly prepared food, out-of-stock menu items, and slow service. This doesn’t get easier as you add more locations — you need to level up and design better systems.

So it’s good news that Foxtrot has just hired a new president and CFO, Liz Williams — who was previously the CEO of Drybar and CFO of Taco Bell — to solidify its operations and finance. I look forward to seeing her impact.

Then there’s the broader environment: High inflation that’s causing Americans to spend relatively less at convenience stores, a potential consumer downturn on the horizon, political division, and a stock market that’s not been kind to unprofitable retail innovators. While the S&P 500 is down about 11% from March, Warby Parker shares are down 65%, Sweetgreen shares are down 49%, and DoorDash shares are down 35%. That could limit Foxtrot’s options in the capital markets as well.

On the plus side, Foxtrot’s upmarket focus, while potentially limiting its addressable market, may also serve as an insulator in a downturn. The company says it hasn’t seen any inconsistencies yet in purchasing behavior, and that its merchandising team can always adjust its assortment to maximize demand and respond to trends. Its increased focus on private label also gives it some more wiggle room.

In the meantime, led by chief marketing officer Carla Dunham — who previously worked at Equinox and in the fashion industry — the company is starting to build a brand that’s visible outside of Chicago, years ahead of a national retail footprint.

It’s working with the right people in the food world, such as Cherry Bombe founder Kerry Diamond and Snaxshot creator Andrea Hernández. Its Up & Comers competition, which seeks to identify and support the next great food brands and entrepreneurs, received more than 1,000 submissions this year. Even its merch is pretty good.

So I’ll be rooting for Foxtrot from afar, and I hope someday from nearby. This is the sort of store where I want to spend time and money, and the sort of store that I think can do well in many places. And while its deliberate growth strategy means it’ll probably be years before it’s open in my neighborhood, I think it’s the right pace to keep quality high and navigate whatever weirdness is ahead.

“It’s, like, the exact opposite of the insane venture model,” LaVitola says, “which I think we were penalized for for a very long time, and now probably seems more rational.”

Hi, I’m Dan Frommer and this is The New Consumer, a publication about how and why people spend their time and money.

I’m a longtime tech and business journalist, and I’m excited to focus my attention on how technology continues to profoundly change how things are created, experienced, bought, and sold. The New Consumer is supported primarily by your membership — join now to receive my reporting, analysis, and commentary directly in your inbox, via my member-exclusive Executive Briefing. Thanks in advance.